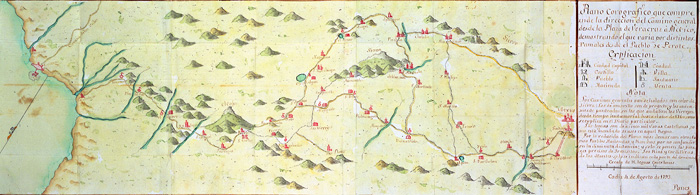

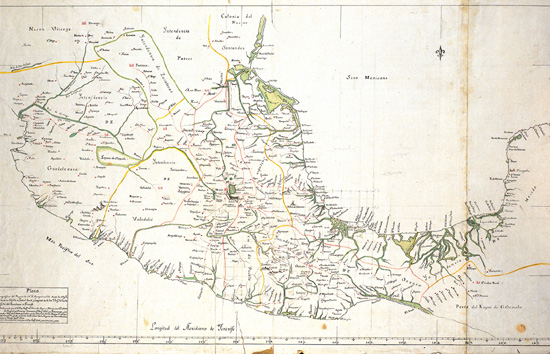

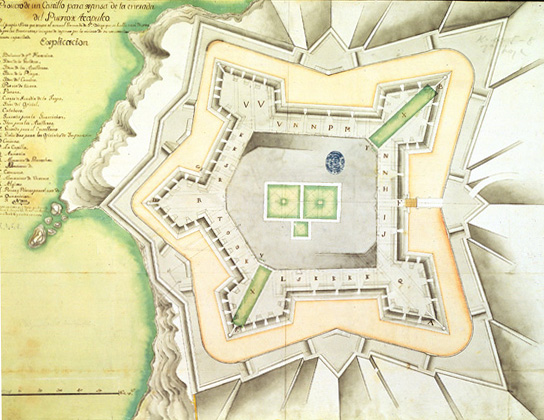

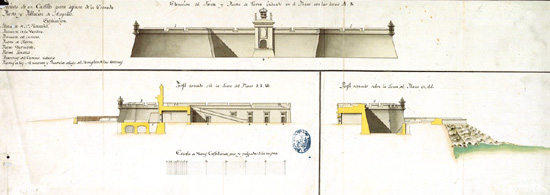

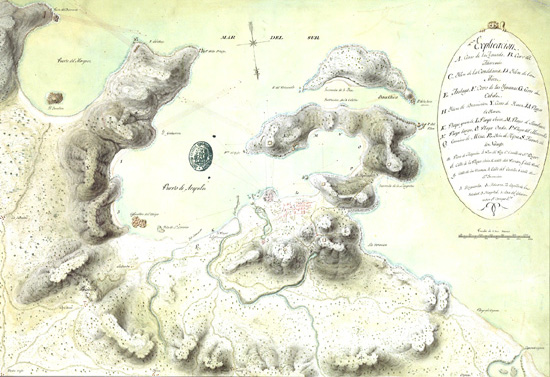

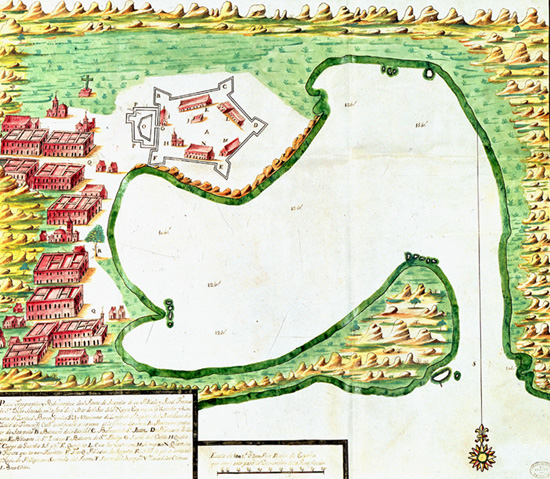

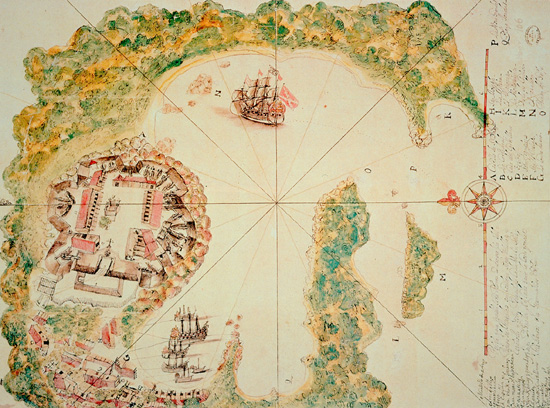

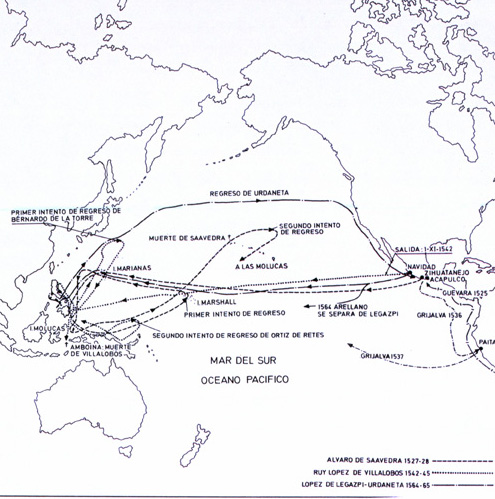

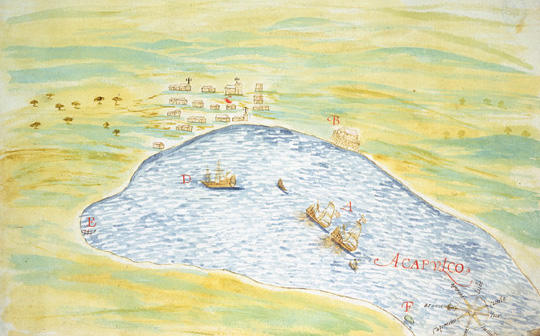

| The bay and city of Acapulco (Mexico). Nicolás Cardona. 1632. BN In 1851, Acapulco was authorized to carry out trading activities with the Orient and became a place of privilege in the links established with the Asiatic archipelago. It was to maintain this role during the lifetime of the Viceroyalty. |  |